A Journey in Music

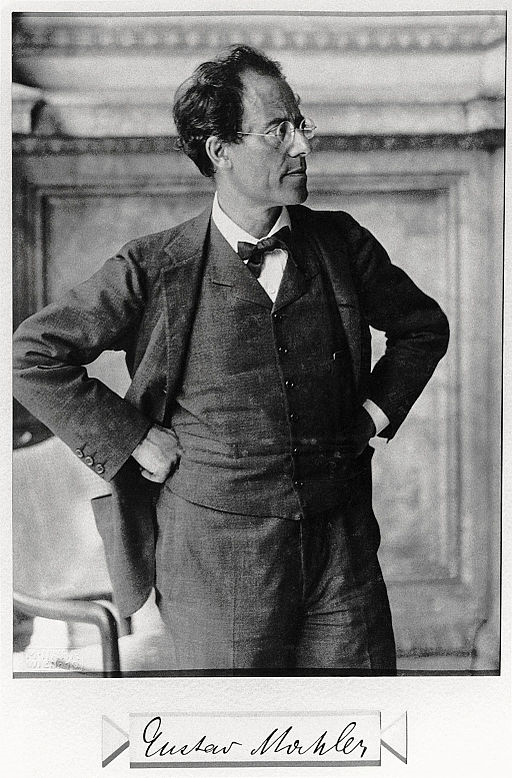

A symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything

Gustav Mahler

Beginning Mahler

The first time I heard Mahler was in 1980 (maybe 1981 or 1982) at the Royal Albert Hall in London. It was full-house, and the only ticket I could get was for the balcony tier—no seats, need to stand throughout the concert. The balcony rail overlooking the stage was filled up, so I resigned myself to sitting on the floor behind the standing crowd. It was the first and only time I attended a concert without seeing the performers. Maybe that would heighten my aural sense and cement the memory of hearing Mahler’s symphony number 5 for the first time; I consoled myself.

All was quiet after the obligatory applause on the entry of the conductor. The silence was suddenly broken by a lone trumpet with a fanfare-like call. Frighteningly, he was all alone, naked and exposed, as the orchestra waited patiently to crash in. I thought that beginning must be the most nerve-wracking 10 bars for everyone; the audience included. If the trumpet cracks, the performance was as good as over. That was the beginning of my lifelong fascination with Mahler’s symphonies—all nine of them, with a tenth unfinished, and an orchestral work with two voices (The Song of the Earth) widely considered to be a symphony as well.

Almost all his symphonies are more than one hour long. Mahler famously said, “a symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything”. Whatever Mahler meant by that, it certainly set the expectation of the listener for something larger than life. After many years of repeated listening, the symphonies have become part of me, sonic worlds that etched deep in the recesses of my mind. Sometimes, I marvel at how a poor kid brought up in Singapore’s Chinatown in the early 1960s in a home with no music background could one day be hooked on the long-drawn complex music of a 20th Century Austrian composer a world away. The answer must be the school band.

Starting in the school band

I think my life would have been quite different if I had not been given a cornet to take home to practice when I was a student at Tanglin Technical School. It took me a while to squeeze a decent sound out of the instrument. After a few weeks, I switched to the tenor horn, which was easier to produce a sound. After a year or so, I realised that horns mostly played “oom-pah-pah” accompaniment, so I persuaded the bandmaster to let me change to the saxophone, which I thought had more melodic parts. It was in the school band that I learnt the rudiments of reading music and realised the importance of playing as a team, for example, not to play too loud to drown out my fellow bandmates!

The school band programme was started in the mid-1960s as one of several co-curricular activities offered to students. It was a far-sighted move during the “survival-driven education” phase of Singapore’s development. According to officials then, the goal of the programme was to inculcate group discipline, esprit de corps and a sense of national identity. However, the most obvious impact of the school band programme was that it opened up a whole new world of music in the lives of young people who did not have the privilege of a music background or a piano sitting at home. I was one of the beneficiaries.

Playing in the school band gave young people like myself a good start towards a path of lifelong engagement with music. Many band members treasured the camaraderie of being in a large musical group but did not continue to develop their interest in music after they left school. For me, a chance encounter with a television programme changed my life, not career-wise, for I did not become a professional musician, but it led me into immersing deeply in music which helped transcend my ordinary existence.

A debt to Leonard Bernstein

It was the late 1960s and early 1970s. My family had somehow acquired a small black and white TV at home, a prized possession, especially for my mother who soaked up all the Hong Kong Cantonese movies and entertainment. The rest of TV time was mostly free for me to explore and I accidentally came across Leonard Bernstein’s series, “Young People’s Concert”, which was aired weekly over the then Channel 5 of Television Singapore. Looking back, I would say it was a defining moment in my life. In that programme, Bernstein bravely took on a full house of American children and teenagers to explain and enthuse about the world of classical music.

Leonard Bernstein was “the great explainer” of music (borrowing the term used to describe Richard Feynman, the famous physicist in about the same era). There was no musical topic too difficult for him to explain. From the mundane building blocks of music like scale, interval, melody, to twentieth-century avant garde—tone rows, atonality and bitonality, etc., he explained these to young people with engaging analogies, stories and demonstrations. Many of his lessons laid a firm foundation in my understanding of music.

For example, his lecture on sonata form was instrumental to my lifelong enthusiasm and appreciation of symphonies and concertos. The sonata form, comprising the logical sequence of exposition, development and recapitulation, is the structural basis of most long, sustained and complex musical works. By introducing this fundamental idea to a young audience in a way that is simple to grasp, he planted the seed to their exploration and appreciation of the vast corpus of classical music. Sometimes, he would even sing and play pop music to illustrate the fundamental foundation of all kinds of music—low brow to high brow. Bernstein’s all-inclusive view of music is one that has left a long-lasting impression on me.

All through these programmes, he gave the impression that one simply could not do without music in life. I was glued to the screen at every broadcast, fascinated by the sound of the orchestra and eager to learn something new about music each time. Most of all, it was Leonard Bernstein, the compelling communicator and teacher par excellence, who kept me tuning in for more each week. Though a well-known composer and conductor, to me, his greatest legacy is as an educator, raconteur, and opinion shaper of classical music. I would be so much poorer in my life if I had not chance upon that television series as a teenager.

My favourite piano concerto

As though one encounter with celluloid Bernstein a week was not enough, the rival TV broadcasting station in Malaysia, then RTM (Radio Television Malaysia) also aired the series (though not in the same sequence) in between the Channel 5 time slot. As there was too much to absorb, I resorted to placing a portable cassette recorder in front of the TV to tape the programmes for repeat listening.

In fact, that was how I came to know and love Mozart’s Piano Concerto in A major (no. 23), which was one of the programmes I had taped and listened to repeatedly. Mozart wrote 22 other piano concertos, but this one always melts me to a puddle whenever I listen to it. Every note, from the first to the last movement course through my brain like freshwater rejuvenating dry and tired lands. It may not top the list of favourite Mozart piano concertos in Internet searches, but it is close to perfect for me. It goes to show how the music that we had experienced in our formative years has a stickiness that lasts a lifetime.

Junior college days

I continued with my school band activities when I went to National Junior College. The conductor of the college band, Ho Hwee Loong, a cheerful, always smiling and encouraging teacher introduced a varied repertoire, including transcriptions of classical pieces (actually mostly overtures), which whet my appetite for classical music further.

I met friends who were also interested in classical music. We used to haunt gramophone record shops after school to browse and listen to snippets, sometimes in rooms specially provided to customers to sample records before they buy. I remember the names of some of these shops—Kwang Sia, Soundscene and City Music, which are now long gone. Naturally, being students, we listened for free most of the time and bought the occasional record to legitimise our visits. In addition, we read the liner notes on gramophone records studiously as they provided a lot of background to the music and artistes. These days, we have the convenience of Spotify but zero information about the context of the music-making.

As my interest in music grew, I hungered for more beyond the school band. I spent quite a bit of time browsing books on music at the National Library, reading and learning many interesting facts and stories which did not help me in my academic studies at all. I wished there was an “A” level subject on music titbits and miscellany which I was sure I would ace the exams. The National Library then had a fair collection of miniature orchestral scores. With those in hand and a gramophone record playing, you could pretend to be the conductor. It was a joy to follow all the notes jumping out of the pages as the gramophone record spun. I learnt a lot about orchestral instrumentation reading scores, of course as a listener rather than a musician. From the score, I know which instrument or combination of instruments is playing in every part of an orchestral work.

Anthony Hopkins’ Talking about Music

There were also some great programmes on the radio which I used to follow keenly. One was a series by Anthony Hopkins (the composer and conductor, not the actor) called “Talking about Music”, a weekly half-hour BBC programme which introduced familiar as well as uncommon pieces of music from Bach to Tippet. Couching his talks like a master storyteller, and using mostly non-technical language, he led listeners through the hills and valleys of a piece of music, leaving them with a yearning to explore further. Most of the time, after listening to an episode, I would want to go out to buy or borrow a recording of the music that he talked about.

His approach in analysing a piece of music was very creative and original, full of wit and humour, so British, and a joy to listen to. I long to hear them again. However, I could only find a few archived programmes on the Internet today. Perhaps the tapes were erased and recycled for use (to save money), otherwise, how can one account for not bringing back to life this treasure trove? Just as Leonard Bernstein had sowed the seed of my lifelong music pursuits, Anthony Hopkins led me to discover many pieces of classical music that formed the soundscape of my mind.

Another British broadcaster I listened to regularly at that time was Harry Mortimer. I cannot remember the name of the programme, “Men of brass” or “Listen to the band” or something like that. The standard of brass band playing featured in the programme was astonishing. It was difficult to believe that the band members were amateur musicians who had day jobs in coal mines, factories and manufacturing plants in Britain. Their virtuosity and dedication to their music inspired me a lot. Brass band music always evokes fond memories of my early exposure to music.

From classical music to big bands, jazz and Chinese music

Western classical music is just part of a broad spectrum of musical arts. The genre spans a considerable range, from Gregorian chants to postmodernism, anchored in between by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartok, Berg, John Adams and others too many to list. There is an infinite number of works for orchestras, chamber groups, quartets, solo instruments, voice and vocal groups in various combination of forms and styles. It will take more than a lifetime to explore even a fraction of classical music. But other musical genres are enticing too, and my musical journey included them as well, sometimes by choice and other times by circumstances.

Many of my friends said I was lucky to serve my national service in the Singapore Armed Forces Music and Drama Company as a musician instead of running up and down hills in the hot merciless sun. Yes, indeed. It gave me a taste of show business and introduced me to big band music. Though most of the musical accompaniment to singers and dancers required only a combo band, i.e. rhythm instruments plus one or two saxophones, trumpets and trombones, we enjoyed ourselves most when we played as an 18 piece big band (like that of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, etc.). I learnt different ways of playing, for example, that the quavers printed on the music sheet are not to be played literally or precisely, but in a lazy way, like a dotted quaver.

Later I also played in the NUS Stage Band and we were lucky to have Professor David Lewis, the principal clarinetist of the Singapore Symphony then (I think he was on loan from Indiana University) to coach us. He made us sound like a real big band—screaming trumpets, roaring trombones and satin saxes. It was an eye (or ear) opener. Only then did we realized the exhilarating power of the big band sound.

From big bands, it was a natural step to take an interest in jazz and appreciating its great practitioners, my favourites being Charlie Parker and Lester Young. Most people associate jazz with its characteristic driving, infectious rhythm and the use of off-beats and syncopation that pushes and pulls us playfully. We sway our bodies, tap our feet and snap our fingers involuntarily. More importantly, the essence of jazz is improvisation. The jazz player has a lot of room to create music on the spot as he plays, but he must strictly follow the chord structure and progression laid down in a piece of music. Jazz holds a simple life lesson for me—you can be very creative despite being highly constrained.

When you entertain soldiers, you also cannot escape from playing popular songs of the day. So a lot of mandarin pop of the 70s reminds me of my short stint in the entertainment business. Earlier in my childhood and teenage years growing up in Chinatown, Cantonese opera was quite a common form of entertainment. I watched them with my mother, aunt, family and a large community of neighbours for free on streets and by the sides of open theatres. Partly because it was imprinted on me while young, I find Cantonese opera music very endearing, it is probably an acquired taste which I think only Cantonese people love and appreciate. From there, it was natural that I also took an interest in the music of traditional Chinese instruments, their ensembles and orchestra. Although its repertoire is not as extensive as western classical music, it has an intimacy and warmth that reminds me of my cultural roots.

There is music in all of us

Music has been part of human existence for more than 40,000 years as revealed by an archaeological find of ancient bone and ivory flutes somewhere in present-day Germany. Music is innate in us. We don’t need to go to school to learn the ABCs of how to feel and enjoy a song or a dance tune. Although music is simply an arrangement of sound waves and patterns of vibrations, it somehow manages to modulate our emotional well-being.

In the last few centuries, through the ingenuity of generations of musicians (particularly in the West), music had developed into a highly sophisticated and abstract form of human expression, capable of conveying intense depth and range of emotions. As with anything that is sufficiently complex, we must make time and effort to unravel its mystery to enjoy the most that it can give. Music is so boundless and extensive that the time and effort needed becomes a lifelong journey. It makes our musical journey more exciting and fulfilling if we have guides such a friend, a teacher or an enthusiast to help us unveil this universal human attribute.

Today, there are plenty of programmes in the likes of “Young People’s Concert” and “Talking about Music” available on the Internet, together with seemingly endless youtube videos of music ranging from familiar classics to the very obscure. Though it is a godsend to have almost limitless choices, in some ways I am glad I had lived in simpler times when I followed the two great masters, Leonard Bernstein and Anthony Hopkins, to build my foundation in music appreciation.

If a composer could say what he had to say in words he would not bother trying to say it in music

Gustav Mahler

Music mentioned in the post

Mahler Symphony No.5 played by Frankfurt Radio Symphony conducted by Andres Orozco-Estrada, recorded 2017

2nd movement of Mozart’s piano concerto no.23 by Helene Grimaud (official video, Deutsche Grammophon)