Memories of Sago Lane: Part 2 – The Friendship Inn

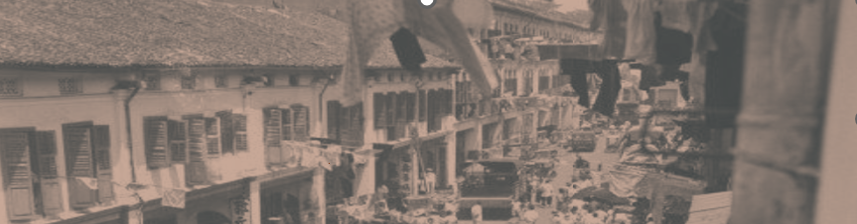

In the distant fog of time, Sago Lane is stripped off its roadside garbage, foul smelling drains, grimy potholes, and walkways littered with puddle of mashed cigarette butts. I was reminded of this after watching some short archival films and photographs of the street in the sixties. Litter was everywhere. I saw a film clip of rainwater draining all kinds of muck and dross on the road while a woman kneeled on the road in prayer. It really jerked my memory back to the filthy living conditions we escaped from decades ago.

Similarly, one also tends to remember the good sides of people, and plaster up their miserly, grumpy, curt, and boorish behaviour that comes from living in a sea of people constantly invading their private space and lives. Memory is like a good painting, leaving out unnecessary details that clutter the story and mood we wish to remember. So, I continue my reminiscing, in the comfort of modern day super-clean Singapore, casting aside the unsavoury truth of the dismal living conditions we endured.

The Landlord

“Yau Chan” (友栈), the shophouse we lived in means “Friendship Inn” in Cantonese. Tenants occupied cubicles which came in varied sizes. My parents had one cubicle while my maternal aunt, who was single, had another. However, I cannot remember much about the cubicles as we hardly spend any time in ours. Instead, we roamed all over the place outside the shophouse. And there were plenty of places to play and explore—the back lane, Kreta Ayer Hill, the main street itself, and further down, streets named Banda, Smith, Trengganu, Temple, Pagoda, Keong Saik, etc.

The Landlord, “Ah Pak” is a middle-aged man who live on his own. I think he has a fruit stall in front of the shophouse. Most important to me, he has an inordinate collection of toys for a man his age. He is either a collector, or he has a secret toy shop somewhere else. My siblings and I are the only children in the shophouse, so we are doted upon. So, there is no lack of toys for me to play with. They range from wind-ups to battery operated mechanical wonders. He also owns the Rediffusion set in the small living area which provide music and radio dramas that form the sonic background of my childhood.

The yong tau foo auntie

The shophouse has a long dim corridor separating two rows of small cubicles. This leads to an open-air communal kitchen where the din, heat and smells mix with loud sing-song chatter and colourful Cantonese swearing typifies the cramped living environment of Chinatown shophouses in the 1960s.

Most of the tenants are women, half of them tie up their hair in a bun. One of them, Seng Hoe, sells yong-tau-foo in a pushcart. She occupies a room overlooking the kitchen. She is always at the same spot every morning, scrapping and chopping fish meat from baskets of yellow tails. She slaps the fish meat in a large metal basin repeatedly to make the fish balls firm and springy—a technique I have since adopted for all sorts of mince I prepare. Her’s is an OMO business, as are most of the food vendors at that time. No supply chain then. She buys all the ingredients from the market, clean and cut them, make the stock and dipping sauces, prepare the stove, push the cart to the streets, serve the customers, wash the bowls and utensils, collect the money and push the cart back and start all over again the next day—all without any assistant.

She has an adult son who is unfortunately intellectually disabled or mentally unstable. He is left on his own throughout the day, wanders in and out of the shophouse dressed in his white, often-soiled singlet. Most of the time he is like a shadow hiding in the woodwork but occasionally burst into life with zesty conversation with people, real and imagined. As far as I know, everybody treats him like everybody else or pretends he is not there. Sometimes, he talks to me, and I would pretend I understand what he says.

The community kitchen and toilet

In its full swing, the crowded kitchen is wet and slippery from tenants washing their cooking ingredients, laundry, and everything else (including their body) in large tubs. It is a treacherous place to manoeuvre, especially for a small boy like me. But why do I want to squeeze through there? Because that is the only way that leads to the back lane and hilltop—my playground.

Before the door to the delights of the backyard, there is a foreboding place to cross. No, not obstacles, just the stupefying stench suspended like a dirty curtain in a dark dim passage. The offending smell comes from the toilet on the right which I dare not cast my gaze at, particularly when the door is left ajar. I think I was brought in there once, just once, by my mother. It is worse when the door is not closed as the light illuminates the slimy stained floor and oppressive walls which your eyes inevitably trace a path to the dark filthy squatting toilet hole, the source of all evil smells.

I do all my business in a chamber pot which my poor mother dutifully empty on my behalf every time, presumably in that only toilet in the shophouse. Ditto for my younger siblings. Sometimes I do it at the drain in the back lane, especially at night, something I am not proud of. I always wonder how people can withstand the few minutes they are in there. It explains why my father is a compulsive toilet scrubber when we moved to more hygienic HDB flats. The fear of his toilet turning into the Sago Lane version must have weighed heavy on his mind.

Back lane activities

The back lane, a road shared by the row of shophouses is a dream place for every child. There is hardly any traffic, just the occasional scooter and bicycle. It is wide enough to play hopscotch and badminton, long enough to race and cycle, and has sufficient nooks and corners to play hide-and-seek. It is shady most of the day since it runs along the foot of Kreta Ayer Hill, which blocks the harsh sun.

In the evening, when the weather is good, residents bring out their stools to eat dinner, which typically consist of a plate of rice with bits of meat and vegetables. Mothers run after their naughty children to squeeze spoonful of food into their mouth while they play hide-and-seek. As dusk approaches, the women folks stay on to enjoy the breeze, gossip, and banter. The men climb up to the hill, where there is a community centre. Some gather around a professional storyteller with a lit joss stick and a bell to time his fee collection. I am never near enough to hear the stories, but they do not seem more exciting than Lee Dai Soh’s.

There were many more occasions to pray and give offerings to the Heaven, deities and ancestors during my childhood compared to today. During these celebrations, neighbours spill out into the back lane to set up tables for praying. On mid-autumn festival, children holding lanterns form spontaneous processions up and down the lane while the adults enjoy their mooncakes, small taros, and pomelo under the bright moon light. There were only 2 types of mooncakes then, with egg yolk or without, not like the bursting variety we have today.

There is also this funny looking fruit/vegetable call ling kok, meaning horns of a bull in Cantonese (water caltrop) that is hard to break and has so little flesh in it that it is hardly worth the trouble to eat it. And it does not taste that fabulous either. For some reason it is always associated with Lantern festival. A more delicious food associated with this festival is river snails stir fry with garlic and black bean sauce. It is messy to eat—you lift open the flap and drive a toothpick into the shell to dig out the delicious morsel.

The gravity of Sago Lane

Later, my parents were allotted a one-room flat in Tiong Bahru and we moved to a bigger living space. Big is relative. There was no bed nor mattress. The large piece of hard board we slept on every night occupied almost the entire flat. I do not have many memories of this place as we were hardly there. We were always in the shophouse in Sago Lane, unable to escape its gravity. The excuse for being there was my maternal aunt who was still a tenant as she had a vegetable stall a few streets away. Thus, my early teenage years were spent in the Street of the Dead.

My maternal aunt

My aunt was not married. Her hair was combed into a bun, which I vaguely understood then as a sign of pledging not to marry. The custom, known as “soh hei” in Cantonese (meaning combing up) is quite common among women in Chinatown then. Though curious, I had never asked her why she chose to be a spinster. Nevertheless, she is a happy person who laughs easily, invariably revealing her one gold tooth. Often, she has a lighted rolled cigarette dangling from her mouth which miraculously stays in place while she talks. Sometimes, with her permission, I will roll up the cigarettes for her to light up. For a small boy, it is fun to squeeze tobacco into tiny paper and roll it up in a long cone without it falling apart. Despite my early association with cigarettes, I have never been tempted to smoke.

Her vegetable stall is just a roadside area demarcated for different hawkers. She shares her business with a close friend. Her “territory” is quite sizeable compared to others in the same street. Many large trays of vegetables spill into the middle of the road. She sits on a low stool, weighing scale on one hand and large bowl of coins for change on the other. She dispenses her vegetable like a queen, favouring some with extra bits and arguing to the last cent with the quarrelsome, but always with good humour.

She earns a comfortable living supplying to restaurants in addition to her daily selling at her stall. She seems to enjoy her work as I always see her chatting and bantering with customers like old friends when I visit the stall. It is not a surprise that her business did well. She is a jovial person and relate well with people. I think people enjoy buying from her stall. She is also generous to a fault. I remember hearing snippets of conversation of somebody asking for more time to return money borrowed from her, which she acceded without argument and with understanding. Our family is the main beneficiary of her generosity. Whatever small luxuries we had at that time, like a black and white TV set, refrigerator, even bird nests and valuable herbs came from her pocket. In later years, she even paid for my initial undergraduate studies in the U.K.

Ignorance or bird nest?

But it is a hard life— waking up in the wee hours of the morning to go to Ellenborough wholesale market to get her vegetable supplies and carting it back to the stall by trishaw in the early years, and taxi when her business grew. The hard work plus her heavy smoking must have taken a toll on her. In around mid 1980s, when she was about 70, she was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. I think she had an operation to remove the tumour as I remember vaguely being shown a photograph of the extraction. But my memory is not clear on this, only that the doctor told me she did not have long to live.

At that time, cancer is an unmentionable word. It would have strike fear and total panic in her, so we decided not to tell her. My mother fed her bird nest soup almost every night as she believed firmly that bird nests soup can repair whatever that is broken in the body. Miraculously, she recovered! Whether this is due to her ignorance of her illness or daily consumption of bird nests, nobody knows. She survived for more than 10 years and passed away while suffering from dementia, a misery she does not deserve.

She gives generously to us, and I suspect to others as well. She lives for her work at her vegetable stall, enjoying the camaraderie with fellow stall holders and customers alike. Even when she was very sick in the last few years of her life and visually compromised, she insisted on running her vegetable stall. When I visited her stall, I got disapproving glances and sometimes hostile comments from her customers for letting her work in her deteriorating health. But she was insistent. She has no reason to live without work. It is not for want of money, but for the satisfaction it brings, almost like what we call ikigai today.

A memorable childhood

It is common belief that our childhood experience has a strong bearing on how we turn out in adult life and beyond. People often point to a traumatic childhood to explain current negative behaviour. I am fortunate to have a happy childhood, though this is in retrospect, since one has no reason to reflect on one’s state of happiness while living it, especially if one is a child. Whether I look at my childhood past with rose-tinted glasses or not, I remember my childhood with fondness. I had freedom to explore and experience the rich tapestry of life woven from unyielding spirit of early Cantonese immigrants struggling to live a settled life; and places filled with vivid, almost exotic scenes, sound, smell, and flavours lost in the march to modernity.

Despite the palpable hardship and material scarcity all around in my growing up years in Sago Lane, there was an air of optimism that life will get better, and that is what all children should grow up with.