Memories of Sago Lane: Part 1: The Sounds of Childhood

In the heart of Chinatown today stand the less exciting remains of Sago Lane, “the Street of Dead People,” or “sei yan kai” in Cantonese. Originally a 250-metre-long street stretching from South Bridge Road to Keong Siak Road, it was cut into two in a massive do-over in the 1970s. Unfortunately, only the duller part of the street, the one leading to South Bridge Road, survived. The life and soul of Sago Lane, near to Keong Saik Road, was completely demolished to make way for the monolithic concrete block that is now Chinatown Complex.

The sound of memories

In the early 1960s, I lived with my parents and siblings in a shophouse called “you zhan”(友栈) in this part of Sago Lane. It was the centre of my world—bustling, noisy, colourful and lively. Unfortunately, I am not able to let the buildings and lanes that marked my formative years speak to me again. There are no moss-covered walls, wet and dirty pavements, and secret nooks and corners that cue my memories to the past; not a single mark or artifact that I can anchor my childhood stories to—no vibes, as people brought up in the 70s would say.

Remembering is a kind of time travel. It brings us back in time vividly—sight, sound and smell glued together to relive the experience of once upon a time. The places where remembering brings us depend on cues we encounter serendipitously or when we exert deliberate effort to do so. Just as Proust wrote famously on how the taste of a small cake dipped in tea can conjure up vivid memories of the past, perhaps sounds of the past can do the same trick.

One of the memories that brings me back to a round marble table with a Rediffusion set on an unreachable shelf in a poorly lit room in the shophouse, is a mysterious piece of music. I have a strong memory of sitting on a chair, my hands on the tabletop, listening and being mesmerized by that piece of music. Of course, I do not know the name, as I was less than 10 years old. But I remember the music made a strong impression on me. It was mellow, sonorous, full of pathos and longing, but not hummable. All I can remember is that it is an instrumental. Later, when I was more musically informed, I thought it might be played by a bass clarinet or a baritone saxophone, or maybe a bass flute. When I was in my early youth, I would have recognized it if I heard it again. I did try to search for it, without success. Now, decades later, I do not think I would recognize it at all. For what remains with me is the medium, not the message; the envelope, not the letter.

Tales from Rediffusion & clandestine radio

Rediffusion then was a kind of cultural transmitter, thanks largely to Lee Dai Sor, the well-known Cantonese storyteller of the era. I always associate the Cantonese song “Thunder in drought season” (旱天雷) with him, as he used it to begin one of his programmes. His daily broadcasts of stories about heroes and villains in ancient China seemed to last forever, cliffhanger after cliffhanger. I became familiar with many Chinese historical characters at an early age and unsuspectingly, imbibed notions of personal integrity, courage, perseverance, and righteousness following their adventures in the ebb and flow of Chinese dynasties.

In the evenings, when tenants in the shophouse come home from work, they listen to Cantonese radio dramas on Rediffusion. It was from these dramas that I first encountered this amazing sleuth called “Fuk Yi Mo Si”. Through keen observation and superb logical deduction, he was always able to solve complicated crimes. This is of course the famous Sherlock Holmes translated into Cantonese. I was only able to put two and two together much later in my adolescence. I did look for his address, 221 Baker Street in London, when I was a student in the UK, of course without success!

Besides Rediffusion, some folks here also listen to clandestine broadcasts from Radio Peking. You know because the volume is always turned low, or they have their transistor radios uncomfortably near to their ears. My father was one of them. I knew it was not Cantonese that spilled out of the radio, but some foreign-sounding Chinese. And the theme music sounded really uplifting. I believed I heard “The East is Red.” It has a very catchy awe-inspiring melody, guaranteed to turn any China sympathizer into a fervent communist then. It is incorporated in the climax in the fourth movement of the Yellow River Concerto. Listen to it if you want to know the power of this music.

Tabacco pipes & violin prodigy

The official Chinese name for Sago Lane (沙莪巷), whether you say it in Mandarin or Cantonese, does not ring any bell for most people, yesterday or today. To me, it is merely a street sign stuck high on the street wall, which no one notices. Everyone refers to this place as “dead people street” (sei yan kai) by virtue of the numerous funeral parlours in the area in the sixties. There were also many death houses, where sick people came willingly or unwillingly to live out their days. I read that these morbid lodgings were banned in 1961—I was 6 years old then. However, even after that age, I remember seeing old people continue to live in cubicles in our neighbouring shophouse. Though it was not a death house, it seemed to serve as one, as I hardly see anyone leave their cubicles. I wandered in the dark corridors a few times. Many of them (all men) spent their time smoking tobacco in their cubicles. They used thick bamboo pipes, not the skinny metal type that you see in museums and movies. They made awful gurgling sounds that I still find nauseating when I think about it today. Think of a basson struggling to reach its lowest notes.

In front of this neighbouring shophouse, occupying part of the five-foot way is a stall called “Bao Lei” after the owner, a late middle-aged man with a distinctive salt and pepper beard, which he strokes often. He is a knife and scissor sharpener. Bao Lei in Cantonese means “guaranteed sharp.” It is probably not his real name, but his surname is Lee or Li. He is always in a sleeveless singlet, the de rigueur attire for men here. I often find him in heated conversations with his neighbours, though not in a bad way. At least he was kind to me. I heard from neighbours that his son, probably half a decade older than me, is a violin prodigy whose talents were discovered while fiddling on a toy violin in front of the shophouse. The son became quite famous and was sponsored to study music in the UK and later became the leader of Halle Orchestra in Manchester. Of course, I only knew this when I was older. But when I was young, I heard from gossiping neighbours about the boy wonder.

Bao Lei himself seemed to lead an interesting life. I heard he was active in political marches and demonstrations against the authorities then. I vaguely remember seeing him holding a protest placard with an angry and defiant look. Later, I learned from neighbours that he was detained several times for his activities. In the late fifties and early sixties, Chinese student activism was strong and often associated with pro-communist ideology. I was too young to understand anything then, but there were certainly people here who were involved in these groups. I remember once, there was a commotion, and some people were running in and out from one shophouse to another. Among them was a secondary school girl in white uniform who lived a few shophouses away. We know the family fairly well, and we kept in contact long after we moved out of Sago Lane. If my mother is alive today, she could probably tell me the whole story and more without blinking her eyes. Alas, I was not so interested in human stories then, not even in my late adulthood. So, I missed a whole cartload of interesting tales of Sago Lane, which I regret while writing this.

Funeral music

Walking further down from Bao Lei’s stall (towards Banda Street), one reaches the funeral parlours and shops selling funerary products. This part of the street is busy most of the time. At night, people attend wakes and sit at tables playing mahjong or just whileing away the time crunching peanuts and cracking melon seeds to nibble, while Taoist priests chant mellifluously at regular intervals. Sometimes when I go out for a walk with adults, I am always reminded not to look into the parlours to avoid seeing coffins and “dirty” things that will bring bad luck. However, the well-lit place looks more festive than spooky.

In the morning, hawkers take over the place for a short while before it is cleared again for the funeral processions. If the street exists today as it was then, you will surely see tons of tourists lining up to watch funeral procession go by. It is an elaborate affair, sending off the dead. Everything in the procession, from the decoration of the hearse to the mourning suits worn, the paraphernalia of funerary accessories like paper houses and Mercedes Benzes, the loud wailing, the banners and lanterns, is full of symbolism of Chinese culture only a Taoist priest can explain. I had a taste of this in a water-down version at my parents’ funerals many years later.

If I am there in the afternoon, I cannot help but drop everything I do and stand at the veranda to watch the parade go by. I was more attracted to the noise and contradicting sounds of the parade. At one end, Taoist priests clad in traditional garb and head gear chant to the accompaniment of suonas, drums, wood blocks and cymbals. I find the chants and music quite mesmerizing. If there needs to be music to guide the departed soul through the gates of Hades, this must be it. The melody and rhythm are so infectious, like earworms that stay beyond their welcome.

At the other end, a brass band blares out incongruous western tunes like “Colonel Bogey”, and “When the Saints go Marching in”, probably to add noise to the occasion. To call it a brass band is a bit too generous. Usually, it is just a 5-piece ensemble comprising 2 or 3 wind instruments (usually trumpet and clarinet, sometimes a trombone and saxophone), and percussion (bass drum, side drum and clash cymbal—a must, to achieve the desired decibels). But at least the bandsmen wear uniforms, with peak caps to boot, though they are often dressed carelessly. In case people think it is rude to make a racket of a noise at sombre funerals, one should be reminded of Chuang Tze (a Taoist sage 2,500 years ago) who banged on pots and pans, and sang loudly at his wife’s funeral, for he believed that death is also a celebration too.

Gang fights and hungry ghosts

Sometimes, the street can be violent. One night, I was with my parents inside the shophouse when sounds of crushing glass and clanging metal from a distance started seeping in. Immediately, the landlord frantically called for residents outside to come in and then violently shut and bolt the door. We were all holding our breath as the sound comes closer like a crescendo until you can hear the loud stereophonic sound of broken bottles, shouting, screaming and clashing parangs and weapons. Then, like a gradual decrescendo, the violent sound melted away until all is quiet outside. The landlord then unbolts and open the door as though a thunderstorm had just passed. I have no idea of what happened—possibly a gang fight. Gangs were rife then, and on the streets, you have to stay away when you see the slightest hint of trouble—not me though, I was just a child, everything around me was rosy and worth exploring.

It is on the same street that ghosts wander, or so we believe, during the seventh month (lunar calendar) Ghost Festival. During this time, all kinds of ghosts, old and young, from hell and elsewhere, flood the mortal domains on their annual time off. Though it is celebrated for the entire month, the 15th day is the most important date, when ceremonies are held to burn offerings to the ghosts. On the night before, families prepare the incense papers. Usually they sit in a circle, talking as they work, watched over by a lit joss stick. Metal-coloured incensed papers are folded into ingots of gold and silver. The adults say they will turn into real gold and silver in the underworld, so the more you fold, the more they get.

On the next evening, the whole street is filled with families giving offerings to appease, give blessings and send fortunes to their deceased relatives. They empty the sacks of silver and gold ingots onto the road, piling them as high as possible. Millions and billions of hell money are then heaped on the incensed paper hill. By this time, groups of children would gather in front of the heap, waiting for it to be lighted, for that is when fistfuls of coins (real money) are thrown over the flame. The falling coins clatter with wind-chime-like sound, spin and roll around as children use their skills to collect as much as they can. I am sure some ghosts are involved too. Sounds like a madcap, but it is quite orderly.

Cantonese opera

It is also around this time in the seventh month when the opera troupe comes to town to perform at Kreta Ayer Hill. The hill comes alive, first with the busy construction of a stage and then a large canvas-roof shelter housing diners in hundreds of round tables. I am probably exaggerating; a small boy sees 10,000 soldiers when there are only 100. A loose fence of wooden poles forms around the shelter as a barrier to prevent non-paying guests from sneaking in. Once ready, many residents start to bring wooden crates, timber planks, and chairs to erect their own viewing platforms around the barrier. They even put up flat trampoline canopies in case it rains. The platform is quite high, at least 4 feet, and is solidly constructed. I was not aware of any tuft disputes; everybody seems to know where to stake their territory.

Thus, begin almost a month of free entertainment nightly for poorer folks like us. Everybody is a Cantonese opera fan, knows all the stories and meaning of the stylized gestures and movements. They are basically 2 types of Cantonese opera, “man” (文) and “mou” (武). “Man “refers to stories that focus on relationships, love, human foibles and are often sentimental. “Mou” operas are mostly about war, conflict, strategies, grandeur and is full of male energy, with a lot of action, weapon twirling and somersaults. Naturally, most of us children prefer “mou” as they are more of a visual treat with many characters dressed in elaborate costumes poking at each other with their spears or swords all the time. It is also noisier, with a full array of percussion instruments adding exciting drama to the action. Played well, the Chinese percussion ensemble can send you into a dizzy. You cannot grow up in this kind of environment without Cantonese opera tunes embedded in your brain for life.

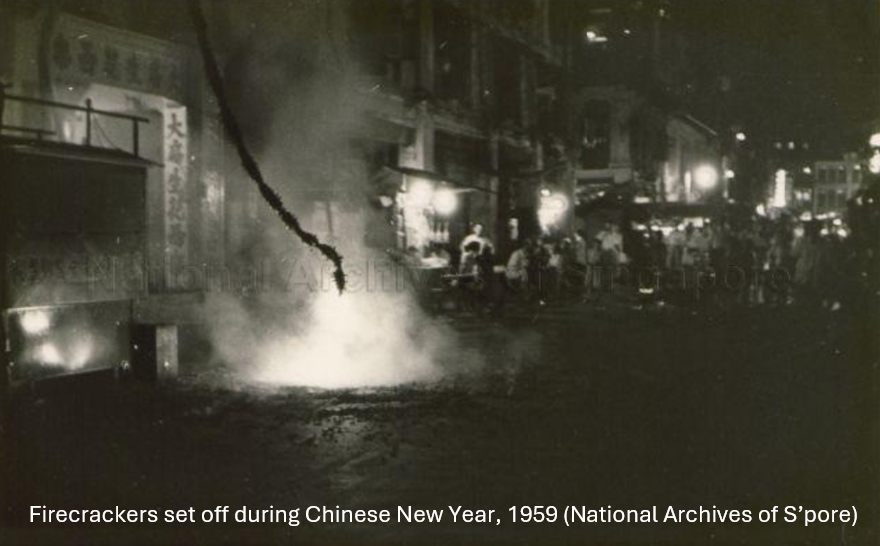

Firecrackers

And finally, the story of my childhood soundscape will not be complete without the sound of firecrackers (banned in 1970). On the arrival of Lunar New Year at 12 midnight, someone, somewhere, would light the loudest sounding firecrackers to rival the fiercest crackling of lightning and thunder. This is followed by a deluge of minor firecracker bursts set off by almost all households. Then, a peaceful calm descends on the street as families prepare for the festivities to follow in the morning. Sounds of firecrackers will mark the remaining 15 days of the new year, reminding us to be joyous and hopeful.

There are a wide variety of firecrackers, ranging from small nail-size bangers to rockets that slice through the sky. I cannot remember where we obtained them, but our landlord seems to be the chief supplier. Most of us play with the small crackers. You hold a joss stick on one hand and the cracker on the other. Light it, throw it and run. For firecrackers that look too menacing to throw, we position it on the ground, sometimes half covering it with a tin can, light it, run, and see how loud and how far it throws the can. At night, the heavy weights are brought out by the Landlord to the back lane. There, we eagerly await as he lights the fuse to set off a blaze of trailing technicolour sparks as it whoosh up the sky. In retrospect, these are dangerous activities, especially in the hands of small children. You can be maimed, or houses can get set on fire. So, it is the right call to have a public ban on firecrackers. But one cannot deny that the disappearance of firecrackers takes away a large part of the festive atmosphere of the new year.

My music

Most of us have stories to tell about our childhood. Reliving a story involves all our senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, etc. Sound is a power sensation, and I try to remember how this is twined up with my childhood memories. Having read much about the science of memory and its working, I know very well that my memories are constructed rather than faithfully retrieved. My accounts here should therefore be taken with a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, some of the memories have such strong visual, auditory and multisensory qualities that I would strenuously deny them as a figment of my imagination!

In the last few months, I was composing a piece of orchestral music inspired by my childhood days in Sago Lane, which led me to writing this post. I call it “Memories of Sago Lane”. It starts with the mysterious tune, which I cannot remember; so I made it up for the bass clarinet. I also incorporated brief snatches of a Cantonese opera tune, “The Flower Princess” or “Dai Lui fa” and “When the Saints Go Marching in”, often played by the funeral bands. I also try to express the hustle and bustle of life then and the joy and happiness of a 10-year-old child in the 1960s. The attached is the .wav file, which you can click to play and enjoy. It is about 8 minutes long. Unfortunately, Musescore (the software I use to score the music) does not have Chinese drums, gongs and cymbals, so I have to make do with the Western varieties. It sounds better if you listen through your high-quality earbud or sound system!